30 Health, ICTs and the social

Stefania Vicari, University of Sheffield

In 1999 American physician Tom Ferguson coined the word ‘epatient‘ to describe individuals who are “equipped, enabled, empowered and engaged” in their health care decisions. While fighting with multiple myeloma, he advocated for a patient-doctor relationship that could overturn traditional paternalistic approaches to health care and management. Over fifteen years later, now potentially anybody can engage in health debates on social media platforms, with patients’ experiential knowledge often becoming a first port of call for individuals seeking health information. Online – and often with a smartphone in their hands – people talk about health, connect around health and advocate for health. But what are the implications of this digital health socialization?

Digital Communication and Health Discourse

In 2011, American writer Deborah Kogan published the piece “How Facebook saved my son’s life”, reporting on how posting pictures of her ill son on Facebook helped her identify his life threatening condition. This and other cases show that online networking may add to or even partially replace traditional patient-physician consultations, especially in diagnostic phases. In fact, patient-centred social network sites like PatientsLikeMe are now being generated to ease health social networking, for instance to store, share and connect around information on symptoms, therapies, and drugs.

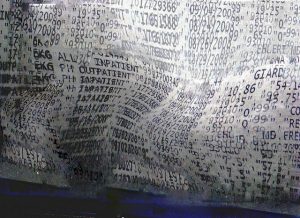

Social media can then clearly ease health information exchange and knowledge building, but how does their commercial networked infrastructure impact the way patient-generated knowledge is made and used? In technical terms, the fact that social media’s network structures shape personalised input obviously affects the supposed “spontaneity” of social networking dynamics. In economic terms, the possibility of personal health data becoming object of commercial use raises ethical issues. Part of the data shared on PatientsLikeMe, for instance, are sold to “partners” but we are left wondering for how long these data will be used by “partners” and – maybe most importantly – how and when these partners’ economic benefit and scientific outputs will pay back to patients.

Social media platforms can ease interactive dynamics among individuals with shared health conditions like in patient communities, but they may also host health debates crowdsourced by a wider variety of contributors. Angelina Jolie’s May 2013 and March 2015 New York Times op-eds on her decision to undergo preventive surgery, for instance, shed public light on her rare genetic disorder – the BRCA1 gene mutation. A Twitter advanced search for “BRCA and Jolie” in the month following Jolie’s first op-ed, returns thousands of tweets where people discuss her decision and the meaning of preventing surgery, but also the implications of having patents on genes, the costs of genetic testing, insurance policies, and rare diseases. How can this online public debate impact patient communities, the general public and, more specifically, health policing and health cultural understandings?

Digital Communication and Health Activism

Health discourse dynamics may mingle with – or lead to – different forms of activism. A recent case of health protest following offline and online public debate is that promoted by the Italian pro-Stamina Movement, mobilised by patient groups demanding funding for compassionate use of the Stamina stem cell therapy in patients with rare neurological diseases. The case came to the fore when a popular Italian TV programme went on air in February 2013. While medicine Nobel prizes and national scientific committees dismissed the procedure as unscientific and risky, patient groups mobilised “a web-based mass action, with protests, sit-ins and a twice-a-week campaign”. Hence, on the one side, (controversial) mainstream media coverage enacted public debate and online interactions bolstered patients’ activism. On the other side, scientists’ expressed their opinion primarily via scientific journals (e.g., Nature, EMBO). Could then online connectivity help overcome the still strong divide between patient groups and scientific experts, especially in the way they interact – or do not interact – on controversial health issues?

While health activism is nothing new, social movement research has recently discussed the emergence of new forms of protest where individuals fluidly connect and disconnect via online social networking. Bennett and Segerberg suggest that digital networking per-se is replacing traditional organisations, with individuals using their personal narratives – rather than organisation or party membership – to engage first in online networking and then in offline activism. While health communication and social movement research have not yet investigated the impact of connective action on health activism, we may once again draw upon a contemporary example to start raising questions on the impact of connectivity – and connective action – on health activism. In 2010 Stephen Sutton, a British teenager, was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. When two years later his cancer was deemed incurable, Sutton made a wish list of fundraising events and became very active online (stephensstory.co.uk), increasingly receiving mainstream media coverage and public attention. As of November 2015, over one year after his death, Stephen Sutton is survived by the Justgiving “Stephen’s fundraising page” that reports a raised fund of almost 5 million pounds, the “Stephen’s story” Facebook page liked more than 1.3 million times, and the Twitter account @_StephensStory with over 178,000 followers. This means that while historic TV broadcasting events – like US Labor Day telethon – are discontinued because of “new realities of television viewing and philanthropic giving” , personalised digital storytelling is becoming a new source for health public engagement.

The Democratisation of Health?

In a way or another, these stories – from Kogan’s to Sutton’s – all show that digital communication practices can enhance diversified health discourse and activism processes and possibly help transform traditional approaches to health care and management. However, they also show that a series of technical, economic, ethical and cultural questions still need to be addressed to assess the real potential of digital communication in what may be seen as health democratisation processes.

Stefania Vicari is Senior Lecturer at the University of Sheffield. Her research interests include the general areas of digital activism, protest frames, and ehealth/epatients. Her works have been published in a number of journals including Social Movement Studies, Current Sociology, New Media and Society and Media, Culture and Society. She can also be found on Twitter and Linkedin.